Christiane, the genius of biochemistry

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1995, together with Eric Wieschaus and Edward Lewis, for her discoveries on the genetic control of embryonic development.

Her work helped to solve one of the greatest mysteries of biology: how the genes in a fertilized egg form an embryo.

Christiane’s story

I had a happy childhood, with many stimulations and support from my parents who, in post-war times, when it was difficult to buy things, made children’s books and toys for us. We had much freedom and were encouraged by our parents to do interesting things.

[Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard]

Christiane was born in Magdeburg, Germany, in 1942, as the second of five children.

Since childhood, she was interested in observing plants and animals.

After high school, Christiane enrolled in the Faculty of Biology in Frankfurt with the desire to become a scientific researcher. In 1969 she completed her studies in biochemistry and started to work on the morphogenesis of development (the process that causes an organism to develop a certain shape).

In the following years, with her colleague Eric Wieschaus, she studied the ‘Drosophila melanogaster‘ (fruit fly) to identify the genes responsible for its formation. Together they invented a process called saturation mutagenesis, where they produced mutations in adult fly genes in order to observe the impact on offspring. Using this method, as well as a dual microscope that allowed them to examine specimens together, they identified 20,000 genes in the chromosomes of fruit flies.

Their fundamental discovery, published in the scientific journal “Nature” in 1980, had important implications also for human reproduction and paved the way for the understanding of embryonic development, enabling the causes of mutations and deformities even in humans to be identified.

Christiane was the director of the developmental biology department at the Max Planck Institute in Tübingen from 1985 until 2014. In 1986 she received the Leibnitz Prize, the highest honor awarded in German research. In 1995 she won the Nobel Prize for Medicine.

In 2004 she created the “Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard Foundation” to help the most promising young female German scientists and to support women researchers with children.

Her personality

Biology doesn’t use the category of beauty to describe organisms. The rigorous researcher avoids applying it to shapes, colors and sounds, as this category depends on the observer and is linked to subjective sensations triggered by non-measurable qualities of objects considered beautiful. And yet the beauty of plants and animals, as we see it, plays a similar role in nature as that played by art and culture for humans.

[Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard]

In addition to being an extraordinary scientist, Christiane has the sensibility of an artist, with many interests outside of work: she likes to cook (she has even written a cookbook), plays the flute and sings, holding small concerts for her close friends. She has a great love for nature and has a large garden at home, which she looks after herself.

Over the years Christiane has been a mentor for many scientists, who, being trained in her laboratory, today conduct their research independently.

She created the Foundation that bears her name to support women who decide to pursue a career in science, helping young female scientists to balance family commitments with the duties of an independent researcher, enabling them to continue

Her research

Creativity is combining facts no one else has connected before.

[Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard]

Christiane introduced the concept of Great Science for the first time in biology, conducting an ambitious large-scale project on mutagenesis (the set of chemical and physical processes that cause a mutation to occur).

Before she came along, molecular biology was mostly based on experiments that demonstrated principles or that gave general examples: the techniques available and the considerable financial efforts involved obstructed scientists from studying the complexity of many biological systems in depth.

Christiane discovered how genes regulate the development process of an individual egg cell in an entire animal and, with her work, contributed significantly to increasing our understanding of the mechanisms involved in the regulation of cellular transcription.

The relevance of her research is huge, both due the importance of determining the development processes in Drosophila – one of the best-known organisms from a genetic point of view – and because similar genes are present in other species, including humans.

After winning the Nobel Prize, Christiane extended her research to zebrafish, taken as a model for the study of the specific features of vertebrates. Her deep conviction is that the combination of different approaches and systems, in one laboratory, provides a powerful basis for further understanding the development of complexity in the life of an animal.

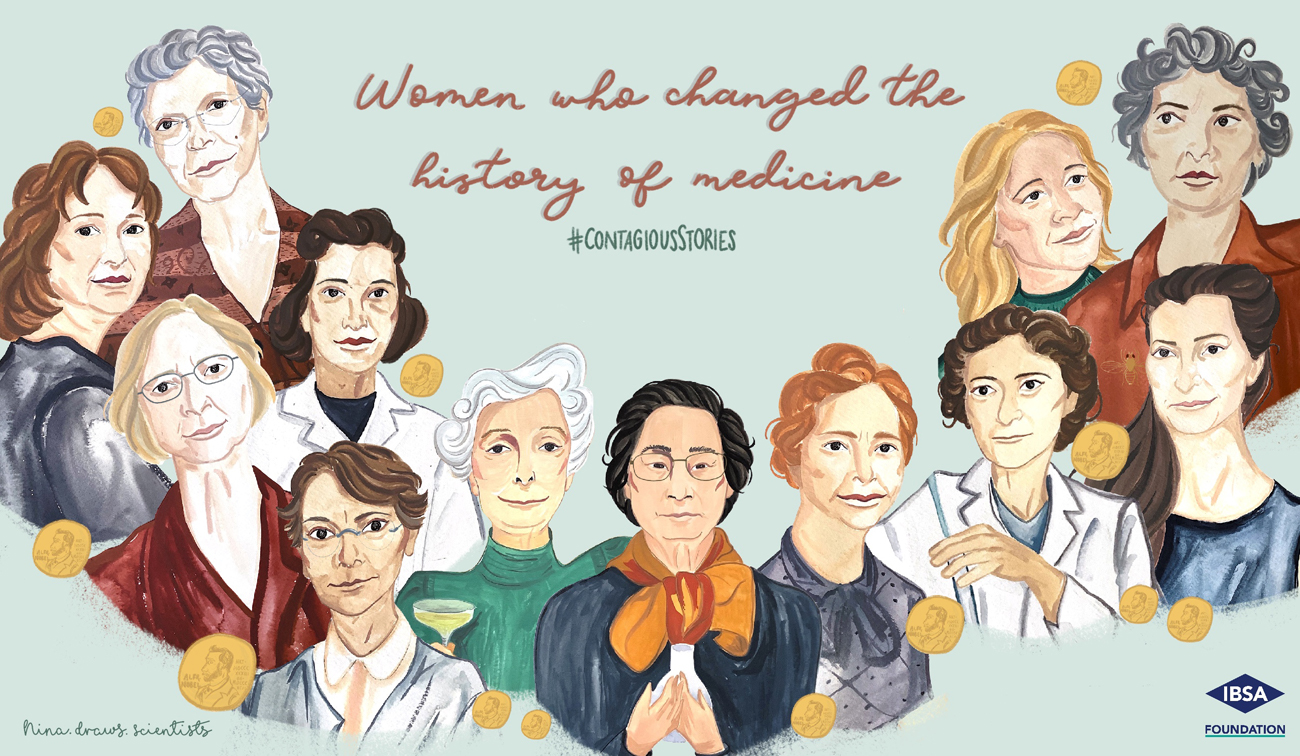

Discover the other stories of the women who changed the history of medicine

Nina Chhita is the artist and illustrator of the Instagram account @nina.draws.scientists, which focuses on contemporary and historical trailblazing scientists, who happen to be women. She initially started the account as a way to discover historical figures, and as a scientist herself, naturally gravitated towards scientists. Articles have since been written about Nina in the BBC news and Mental Floss. Her illustrations have appeared on the social media sites of the University of Oxford, the University of Bath, Dementias Platform UK, and in a YouTube video by Vanessa Hill. She lives in Vancouver where she works as a medical writer creating educational content for healthcare professionals.

Nina Chhita is the artist and illustrator of the Instagram account @nina.draws.scientists, which focuses on contemporary and historical trailblazing scientists, who happen to be women. She initially started the account as a way to discover historical figures, and as a scientist herself, naturally gravitated towards scientists. Articles have since been written about Nina in the BBC news and Mental Floss. Her illustrations have appeared on the social media sites of the University of Oxford, the University of Bath, Dementias Platform UK, and in a YouTube video by Vanessa Hill. She lives in Vancouver where she works as a medical writer creating educational content for healthcare professionals.