We continue to explore digital art, which is now fully part of the discussion on new forms of contemporary art, by looking at those artists whose current work is a kind of rite of passage between ‘traditional’ and ‘new’ digital techniques.

Among these, the British artist Neil Mendoza stands out for his determination and precision, with a work that combines hardware and software, mechanics and electronics, the physical world and the virtual word with device/works whose poetic centre is user participation and involves questioning the changing world together.

Co-authorship as the core of the work

Co-authorship is obviously not just a modern approach. Between the 1950s and 1960s kinetic art already created several works that were mechanical devices activated by users. And it is no coincidence that this movement is a reference for many of today’s digital artists.

The issue is vital, because we are moving not only from the world of hardware to that of software, but from that of the artist as a romantic genius and solitary creator to shared creation. In short, from one to two to many.

The artist is no longer alone, but part of the world in which they create their community.

Neil Mendoza does this by building absurd sculptures animated by special electronic systems: objects that are found, constructed and purchased, everyday things for which the artist has reserved a different (and often ironic and surreal) destiny. It is this ironic vein, in fact, that has led him to co-found the "is this good?" art collective.

This name says a lot about his approach, which goes beyond the ironic and surreal to ask very concrete and ethical questions, with an awareness that ethics (like beauty and goodness for the Greeks) is the mother of aesthetics and therefore of art and the truths it seeks.

Ironic, educational works

However, as is the case for several artists, Mendoza came to art (in his case digital art) through designing video games and advertisements, working on communication and corporate identity for banks and other companies, until one day he realised he could work freely for himself, using the same tools to create works of art and ask questions of himself and others.

He is not searching for truth alone, and in fact many of his works have a strongly educational purpose and are often targeted at children and students. One example is the work Mechanical Masterpieces, created for the Pittsburgh Children's Museum, where a collection of images of paintings from the Renaissance to the present day are animated by turning cranks, pulling strings and flicking switches.

Or in Hamster Powered Hamster Drawing Machine, in which a mechanical drawing device is operated by a hamster and therefore draws a hamster. It is basically a hamster self-portrait machine, says the artist, with a focus not only on men and women, but also on nature.

A similar work is Fish Hammer, in which the movements of a goldfish trigger a hammer outside the aquarium that destroys miniature furniture, chairs, sofas, tables and beds. It is also an ironic action and, in the words of the artist, "a metaphor for a kind of small revenge against man who destroys an animal’s habitat". He continues: "I make ironic works out of these serious problems, so as not to be too didactic and because through irony they fix themselves much more deeply in our psyche and memory." In fact, his work is generally fuelled by unpredictability and absurd randomness, but this does not make it any less intense. In the artist’s words, "It’s like Terry Gillian's cartoons, or the traps that Wile E Coyote builds for Road Runner, or Monty Python's films in which reality is distorted, made surreal in order to be able, as the surrealists did, to enter the human subconscious more effectively".

The interplay of physical and virtual

This is also clearly seen in the Robotic Voice Activated Word Kicking Machine at the Leonardo da Vinci National Museum of Science and Technology in Milan, in partnership with the IBSA Foundation.

It is a physical and virtual device/work, in which the words we speak into a funnel are sucked up and appear visually on a screen, only to be kicked around by a mechanical foot that sends the meaning of the sentences into the air, like the free words of the Futurists.

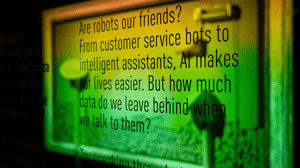

This clearly shows that humanising similar digital processes and systems is an area ripe for artistic exploration. What Neil Mendoza wants to do with his work is make us reflect on the use of the language that we now use so widely with electronic devices – like Alexa, Google Home and Siri. These words, the artist continues, “disappear into a sort of black hole, where my relating them to a physical, material part is the desire to give them a life beyond the screen."

And so, with his work, he concludes by arguing that “artists must play a role in where and how digital technology will end up” and their work will help us light the way and emerge, as always, from the dark side of technology.

By Giacinto Di Pietrantonio