Tu Youyou, the Nobel Prize for her work on malaria

Tu Youyou won the Nobel Prize in Medicine, together with William C. Campbell and Satoshi Omura, for her important work on the cure for malaria.

She is the first Chinese scientist to have received a Nobel Prize in a scientific category, without having a doctorate, a medical degree, or training abroad.

Tu’s story

Every scientist dreams of doing something that can help the world.

[Tu Youyou]

Tu was born in Ningbo, a city on the east coast of China, in 1930. Her family strongly believed in the importance of education, but when she was 16 Tu had to take a two-year break from studying because she had contracted tuberculosis. When she returned to school, she knew exactly what she wanted to do: enrol to study medicine.

At Beijing Medical College, Tu studied Pharmacology and learnt how to classify medicinal plants, extract active ingredients and determine their chemical structures. When she graduated in 1955, Tu went to work at the Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine, where she would remain for her entire career.

In the 1960s, North Vietnam asked China for help with fighting malaria, which was causing huge losses among its soldiers. The single-celled parasite that causes malaria had become resistant to chloroquine, the standard treatment for malaria. On May 23, 1967, Chairman Mao Zedong launched Project 523 with the aim of finding a cure for malaria.

In 1969, at 39 years old, Tu was appointed head of ‘Project 523’. She decided immediately to travel to Hainan island, in southern China, where there was a terrible malaria epidemic. In those rainforests, Tu witnessed first-hand the devastating effect of the disease on the human body.

When she returned to Beijing, Tu reviewed ancient Chinese medical texts in order to try and understand the traditional methods of fighting malaria. She found a reference to sweet wormword, used in China around 400 AD to treat “intermittent fevers”, a typical symptom of malaria.

Tu and two colleagues tested the substance on themselves before administering it to 21 patients in the province of Hainan. All of them recovered.

The following year, Tu’s team distilled the compound’s active ingredient, artemisinin. Although her work wasn’t published in English until 1979, the WHO, World Bank and UN invited her to present her findings publicly in 1981.

It took another two decades, but in the end the WHO recommended artemisinin therapy as the first line of defence against malaria. In 2011 the Lasker Foundation awarded the Clinical Medical Research Award to Tu, calling the discovery of artemisinin “arguably the most important pharmaceutical intervention in the last half-century.”

Tu won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2015.

Her personality

The work was the top priority so I was certainly willing to sacrifice my personal life.

[Tu Youyou]

As she said herself, as a young scientist Tu felt overwhelmed by the responsibility of the task assigned to her: to find an effective cure for malaria.

In addition to the huge pressure she was under, this challenge had a shocking impact on her family life:

By the time I accepted the task, my elder daughter was four years old and my younger daughter was only one. My husband had to be away from home attending a training campus. To focus on research, I left my younger daughter with my parents in Ningbo and entrusted my elder daughter to a teacher. When I saw them again after three years, my daughters didn’t recognize me.

[Tu Youyou]

A sense of duty, spirit of sacrifice, great courage and tenacity are several of the most evident traits of Tu’s personality. In addition to these there is also modesty: Tu was always reluctant to take credit for her discovery. When she received the Nobel Prize, she entitled her lecture, ‘Discovery of Artemisinin: A Gift from Traditional Chinese Medicine to the World’. But she was proud of her work, and rightfully so.

Her research

The discovery of artemisinin inspires us to approach research through the integration of diversified disciplines. Exploring the treasury of traditional Chinese medicine has provided us with a unique path leading to success, while utilizing modern scientific techniques and approaches are no doubt an effective and efficient way of realizing and expediting discoveries.

[Tu Youyou]

In her training, Tu added her in-depth knowledge of ancient Chinese medicine to her background as a modern Western doctor. This unique combination allowed her to link the best of the knowledge and therapeutic approaches of both these schools.

By the time Tu started searching for anti-malaria remedies among traditional Chinese medicines, more than 240,000 compounds had already been tested for use in potential anti-malarial drugs and none had worked.

In 1971, Tu and her team isolated an active ingredient in wormwood. Initially it didn’t seem to work. But then Tu sensed that the extract had to be prepared with a solvent other than water at a relatively low temperature in order to prevent the active ingredient from being destroyed. When they tested it on mice and monkeys, they achieved a 100% success rate.

Tu then volunteered to be the first human subject to test the drug.

And thanks to her research and her courage, today more than two hundred million malaria patients have received artemisinin combination therapies.

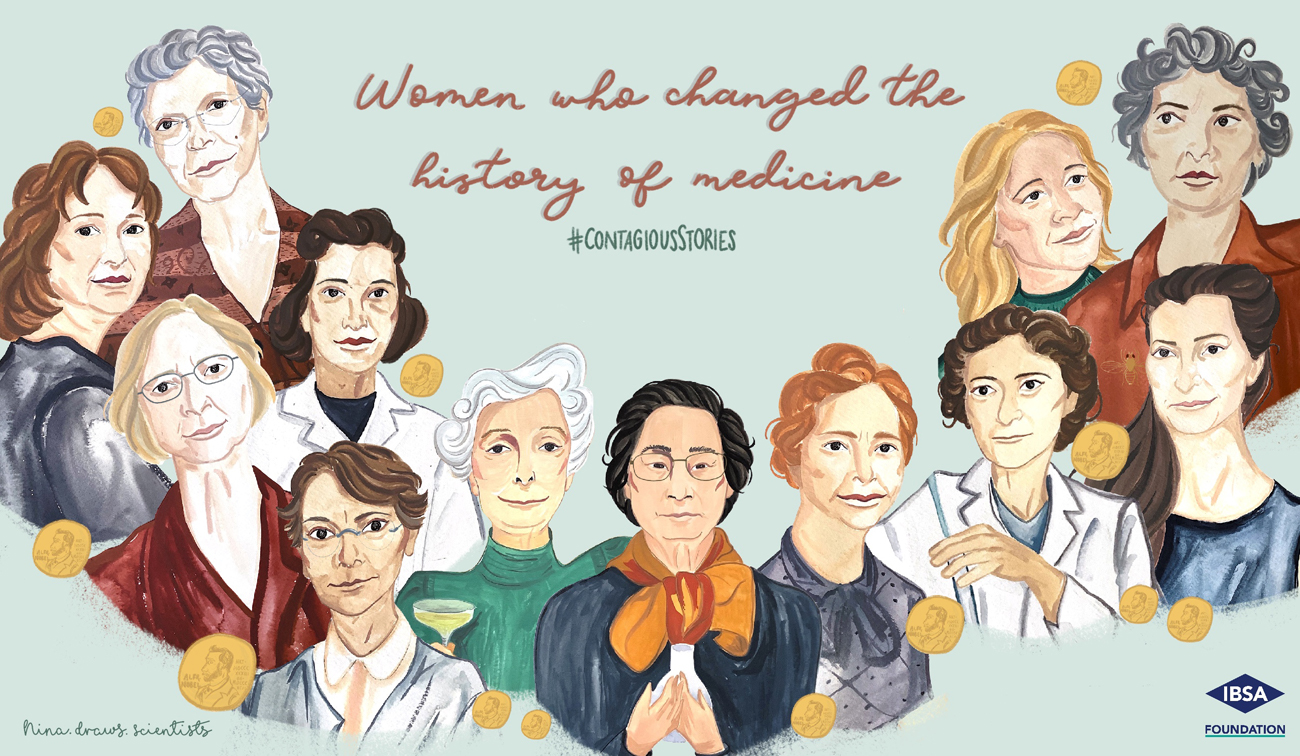

Discover the other stories of the women who changed the history of medicine

Nina Chhita is the artist and illustrator of the Instagram account @nina.draws.scientists, which focuses on contemporary and historical trailblazing scientists, who happen to be women. She initially started the account as a way to discover historical figures, and as a scientist herself, naturally gravitated towards scientists. Articles have since been written about Nina in the BBC news and Mental Floss. Her illustrations have appeared on the social media sites of the University of Oxford, the University of Bath, Dementias Platform UK, and in a YouTube video by Vanessa Hill. She lives in Vancouver where she works as a medical writer creating educational content for healthcare professionals.

Nina Chhita is the artist and illustrator of the Instagram account @nina.draws.scientists, which focuses on contemporary and historical trailblazing scientists, who happen to be women. She initially started the account as a way to discover historical figures, and as a scientist herself, naturally gravitated towards scientists. Articles have since been written about Nina in the BBC news and Mental Floss. Her illustrations have appeared on the social media sites of the University of Oxford, the University of Bath, Dementias Platform UK, and in a YouTube video by Vanessa Hill. She lives in Vancouver where she works as a medical writer creating educational content for healthcare professionals.