Successful tests using “phages” at ETH Zurich. These are viruses that can attack bacteria and be used to both identify an infection and fight it effectively.

Different research groups around the world are focusing their attention on bacteriophage viruses (also called simply “phages”, from the Greek “phagein”, meaning “to eat”), viruses that target and infect bacteria, not humans.

Although they were studied at length during the first half of the twentieth century, seen as possible “tools for fighting certain bacterial illnesses” (the idea was to use phages to destroy the most dangerous sorts of bacteria), the research was abandoned once antibiotics were developed. Now, however, in the face of bacterial strains that are increasingly antibiotic resistant, research into phages has been regaining momentum.

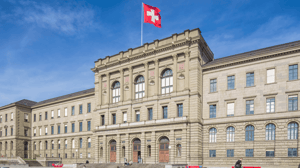

One intriguing example comes from the Institute of Food, Nutrition and Health at the ETH Zurich polytechnic university, which has published two studies on phages in the scientific journal Nature Communications, focusing chiefly on their use (for diagnosis and treatment) in fighting bladder and other urinary tract infections, which affect women especially.

UTIs: a precise diagnosis can be difficult

When a urinary tract infection occurs, one of the main issues is understanding what type of microorganism has caused it, because there are numerous bacteria that can infect the bladder, ureters and kidneys. If the infection is to be effectively fought, the bacterium responsible for it must be identified before a possible remedy can be administered, but this is by no means easy to do, and can take several days using conventional tests (urine cultures, etc.).

It is for this reason that the researchers in Switzerland turned to phages, given that one specific type exists for each individual strain of bacteria.

As they explain in one of the two studies, the microbiologists from ETH Zurich genetically modified those phages that are capable of infecting the three “families” of bacteria most often implicated in urinary tract infections, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella and Enterococcus. Following these modifications, each time that a phage encountered a bacterium during the urine tests in the laboratory, that bacterium would produce a light signal. As they then described in their second article, by using this method, the researchers were able to identify which bacteria were present in the urine of over 200 individuals in just 4 hours, with 99% specificity, high sensitivity (between 68% and 87%) and greater than 90% accuracy.

A tool that is also for treatment

And that’s not all. The infectious disease specialists involved showed that the amount of bioluminescence produced by the bacterium being" attacked” also became, for practical purposes, an indicator of the strength and efficacy of the phage, which could thus also be used in treatment. In other words, the method developed by the researchers at ETH Zurich could be used not only to have a clear picture of the type of infection present (and hence prescribe the most effective antibiotic), but also to provide each patient with a sufficient amount of specific phages capable of fighting that infection, as a complement to the antibiotics themselves.

Additional studies will be needed before we can actually apply these methods in a clinical setting, and regulations will also need to be updated. Given that we are talking about biological materials with unique characteristics, these are extremely complex procedures to develop.

Correlated articles:

https://www.ibsafoundation.org/en/blog/viruses-friendly-against-resistant-bacteria

https://www.ibsafoundation.org/en/blog/virus-phages-against-bacteria-tests-positive