A study of 20 patients severely affected by bacterial infections. Researchers treated them by injecting special viruses, called phages, into their veins, which identified the bacteria and destroyed them.

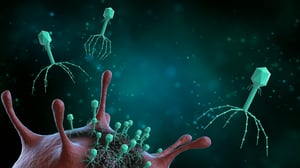

Administering a virus, as if it were medicine, to treat patients with serious infections caused by bacteria. It might seem like a contradiction, but it is real, if the viruses we are talking about are so-called bacteriophages, or simply phages.

These types of viruses, of which there are many on Earth, are in fact ‘designed’ by nature to target only bacteria (not human cells) and duplicate inside them. After this ‘treatment’ the bacteria almost always die.

Several research centres worldwide are trying to identify and select ‘targeted’ phages against the most dangerous bacteria for humans (those that are resistant to antibiotics) and use them as an alternative to drugs.

In reality, there have been cautious attempts to exploit the potential of phages for some time, but so far the results have always been inconclusive, and of little use for therapeutic purposes. Now, however, thanks to major international research coordinated by biologists at the University of California in San Diego, the results of which have been published in the scientific journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, we may have turned a corner.

The Californian researchers started from the personal experience of one of their own, Tom Patterson, who five years ago was on the verge of dying from a bacterial infection that resisted all available antibiotics. Patterson was the first person to receive experimental phage therapy injected into a vein and survived.

The University of California therefore decided to fund a Centre for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics, which designed and carried out the current study.

A focus on mycobacteria

To understand how best to use phages, the authors focused on a large family of bacteria, called mycobacteria, that cause dangerous infections in vulnerable people, such as people with cystic fibrosis and other chronic respiratory conditions. Some of these species, especially Mycobacterium abscessus, are increasingly resistant to antibiotics, to the point that - according to some estimates -they are believed to be responsible for 35,000 deaths a year in the U.S. alone.

Paradoxically, the main obstacle to using phages so far has been their extremely specific nature, because each one focuses exclusively on a certain type of bacterium, which limits their effectiveness in real-world situations where dozens of variants of the same microorganism coexist.

However, the researchers didn’t give up and chose 20 patients (the highest number so far for this type of test) with severe and chronic conditions like cystic fibrosis and identified 55 strains of mycobacteria in their bodies that were resistant to antibiotics, but for which there were specific phages. They then prepared the phage therapy in the laboratory and administered it either intravenously or by aerosol, or both, twice a day for an average of six months. For some patients the period was longer and for others shorter, depending on their response. They therefore checked for both safety and effectiveness in all of the patients.

The treatment appears safe

The most reassuring preliminary finding regards safety: no critical issues emerged for any of the participants, suggesting that therapies of this kind can be administered for a long time. In terms of effectiveness, 11 patients showed an improvement in symptoms or a decrease in bacterial load, 5, on the other hand, did not allow the researchers to reach any firm conclusions, and 4 did not respond to treatment.

Finally, antibodies that neutralised phages (produced by the immune system) were found in 8 patients, and this may explain the partial failure.

All this helps us understand how complex this kind of approach is. A lot depends on the type of bacteria present, and the type of phage used. Both also have to deal with the body's defence system, which may react in different ways. However, the researchers point out, the safety of the treatment, together with its clear effectiveness in some patients in the trial, warrants further studies to define an adaptable, flexible protocol that can be customised and applied.

One of the first steps will be to understand and classify phages further, so that they can then be reproduced synthetically in the lab, in order to create a standardised, precisely dosed treatment. Researchers believe it is worthwhile, partly because the immune system does not seem to be able to block it easily. It also seems to be very flexible in terms of how it is administered and this could be crucial for optimum effectiveness against individual diseases.